In 1980, a book by Warren Craig called “The Great Songwriters of Hollywood”, starts with Irving Berlin, goes through Harry Warren, Jerome Kern, Johnny Mercer, etc., and ends with Livingston and Evans, whom the book calls “the Last of the Great Songwriters of Hollywood”. Like those that came before them, their respectable list of hit songs have all become standards which are still constantly being recorded and performed.

Livingston and Evans both grew up in small towns, and their main contact with the outside world was through radio. Jay Livingston was a DXer, a hobby that no one practices anymore. DXers tried to see how many radio stations they could pick up and then entered them in a log book. Jay found 235 stations before he went off to college. During his kilocyclic meanderings, he heard music from all over the country, and was especially impressed by the big bands he picked up from New York, Chicago, New Orleans and other cities.

His favorite performer was Little Jack Little, a pianist-singer from WLW, Cincinnati. Little Jack Little had a marvelous technique on the piano, which inspired Jay to work hard at the piano to try to emulate him. When he auditioned for Pittsburgh radio stations, he did an imitation of Little Jack Little, which they allowed him to perform on the air.

Ray’s heroes were the big New York show writers, especially Cole Porter. He got first hand experience watching the movie musicals that came to the theatre in Salamancc, NY. He would get the advance programs from this theatre, and always made sure to catch all the musicals. This theatre is now called the Ray Evans Theatre, in honor of the local boy who made good.

Their orchestra at Penn played on cruise ships during Easter and summer vacations, and Jay credits this with giving him his broad experience with all kinds of music. When they stopped in Havana, they bought rhumba instruments from a man on the street, who taught them to play them. That night, they imitated what they had heard in Havana, on the ship, with the three sax players playing piano improvised in Havana rhumba style.

The cruise director, who was the head cruise director of the Holland-America line, got very excited and told them to keep playing until he found a partner. As he danced by, he kept saying, “Don’t stop,” which surprised the band because he had enjoined them to cut their sets to a minimum, to keep him from being stuck with partners he didn’t care for. It turned out that this cruise director was crazy about the rhumba, which other college bands didn’t play. When they finished, he told them, “You can have any cruise you want on this line,” which enabled them to cruise the world during their college years.

When the ship stopped in Buenos Aires, they heard the authentic Argentine tango, which they also imitated, and in Rio de Janeiro, they had their first exposure to the samba, which had not yet reached the United States. And in Trinidad, they heard the calypso, and both Ray and Jay learned how to write for this medium, which purposely stressed a word on the wrong syllable. During their first days in Hollywood, they were invited to a party by the famous King Sisters, which was peopled by greats in the music and motion picture world, and they decided to impress this august assemblage by writing and performing The Hollywood Calypso, about their impressions of Hollywood—”a-ba-lo-ne a-vo-ca-do,” using the style they had learned in Trinidad. This was a big hit, and garnered them many friends. In fact, the King Sisters began singing “The Hollywood Calypso” in their public appearances.

At the end of their last cruise, Ray came into Jay’s stateroom and, to Jay’s great surprise, suggested that they stay in New York and become songwriters. And, thus, the team was born.

During most of this time, one of their songs and ten cents could buy you coffee. Then one day Ray saw a publicity item stating that Olsen & Johnson, then one of the most powerful acts in show business, were looking for new songs for their hit show “Hellzapoppin’”. Unfortunately, that PR item was only true inside the mind of the misguided publicity hack that planted it. But, not knowing this, Ray wrote to Olsen & Johnson and told them that Livingston and Evans had great songs for them. In another stroke of good fortune, Olsen & Johnson had recently hired a new secretary who, not knowing any better, stuck Ray’s letter under Ole Olsen’s nose during a letter-signing blitz, and next thing you know, Jay and Ray were presenting themselves (as the “invited guests” they thought they were) backstage after a “Hellzapoppin’” matinee. Olsen was obliged to listen to their songs, having signed the letter, and thus started a new and very important relationship. They were assigned to write many songs for Olsen & Johnson for numerous charity events, and some songs even made it into “Hellzapoppin’”. One of these, G’BYE NOW, made The Hit Parade of 1941, giving the guys a much-needed shot in the arm (and boost to the bank account). In 1944, Olsen told Jay and Ray that, if they would drive his car out from Chicago to Los Angeles, they could stay at his house. Thus were Jay and Ray introduced into the Hollywood scene.

Olsen & Johnson were making two pictures for Universal, and putting together a new Broadway show, and Olsen suggested that something might come of this for the fledgling songwriting team. But the honchos at Universal weren’t interested in two unknown songwriters, and neither were the Shuberts, who were in charge of the Broadway show.

Olsen & Johnson ultimately went back to New York, but Jay and Ray stayed on. They soon got an assignment writing songs for a picture called “Swing Hostess” starring singer Martha Tilton, at a small, now-defunct studio named PRC. Martha was a Capitol recording artist, and Capitol’s then-president Johnny Mercer (also one of the great all-time lyricists, you might recall) was obliged to listen to the score. He didn’t pick any of the songs for Martha, but one day his office called saying Johnny wanted to do one of the songs from “Swing Hostess”, entitled THE HIGHWAY POLKA, on his nightly NBC radio show. With this foot in the door, they wrote a special song for Mercer called THE CAT AND THE CANARY. They sat in his office for three straight days before Mercer would see them. When he finally heard it, he liked the song and sang it on his radio show. They then wrote another song called BAND BABY for Mercer. This time, they were ushered right in. Mercer sang this one on the show, as well as mentioning Jay and Ray by name before each of the three nightly performances. Publicity….the grease that glides the wheel.

Still in 1944,Louis Lipstone, head of the Paramount Pictures Music Department, asked Johnny Mercer if he knew any young songwriters who would write a song on assignment (and on spec) for Betty Hutton. Johnny suggested Livingston & Evans (the “and” having now been traded for the more household-name-like “&”). They wrote 3 songs for this shot, as this was their first assignment from a major studio and they didn’t want to blow it. But Lipstone told them they could only play one song; the only one he liked. The boys played it for Buddy DeSylva, a prominent Paramount producer (and a notoriously great audience). He laughed at every punch line, often pounding the table in delight, then turned to them when they finished and said “I don’t like it”. Thud…welcome to show business.

Jay and Ray, totally disheartened, had to wait in the outer office while the head of the Paramount Pictures Music Department, Louis Lipstone, did some business with DeSylva. They knew what was going on in there. At some point, Lipstone said to DeSylva, ”Buddy,they had another song that I didn’t like, but maybe you should listen to it”. Buddy looked at his watch and thought about lunch. Nope…too early. O.K., send ‘em in for one more. This was the turning point for Livingston & Evans.

The song Buddy DeSylva chose instead of an early lunch was called A SQUARE IN THE SOCIAL CIRCLE. It ended up being sung by Betty Hutton in “The Stork Club” and she also recorded it. A few weeks later, Louis Lipstone called them into his office and asked if they would like to work at Paramount, writing songs on assignment for the musical short subjects. He said he could only afford to pay them $200 a week, but that, if they did well, maybe they could improve upon that. Jay and Ray had never seen $200 at one time, but they played it cool, saying that would be O.K. On their way out, Jay turned to Ray and asked, “Is that $200 apiece or $200 for both of us”? Ray said, “I was afraid to ask”. When they got their first checks, they each held $200 , which felt like a million to two young songwriters in 1945.

During their first six months on the job, they wrote songs for all the musical shorts and were assigned to write 3 songs for a Bob Hope picture: “Monsieur Beaucaire”. This started a long relationship with Hope, which lasted the rest of their lives. Over the years they wrote songs on assignment for twelve Bob Hope pictures, and a wealth of special material for his stage act and TV shows.

During their first six months on the job, they wrote songs for all the musical shorts and were assigned to write 3 songs for a Bob Hope picture: “Monsieur Beaucaire”. This started a long relationship with Hope, which lasted the rest of their lives. Over the years they wrote songs on assignment for twelve Bob Hope pictures, and a wealth of special material for his stage act and TV shows.

During this time, a song called (written for a film entitled “Why Girls Leave Home”) was nominated for an Oscar for Best Song. Also during this intial six month period, a picture came along entitled “To Each His Own” (from a John Donne poem by the same name). The studio hated the title, but the producer, Charles Brackett, insisted on it. Victor Young, who wrote the background score, was asked to write a title song to help sell the picture, but he refused, saying the title was a dumb idea based upon a phrase which was unknown at the time. Enter Livingston & Evans. As they said in their And-Then-I-Wrote act, “We were so eager that we would have written COME TO US JESUS IN E-FLAT if they had asked us to”.

Considering this assignment another golden opportunity, they did their very best and came up with a song that ended up being the #1 Song of the Year. At one point, for three solid weeks, five of the records on the Billboard Magazine Top Ten Record Sellers were cover versions of TO EACH HIS OWN, by Eddy Howard, Tony Martin, Freddy Martin, The Ink Spots, and the Modernaires.

Then followed GOLDEN EARRINGS, lyrics by Jay and Ray to a melody of Victor Young’s for the Marlene Dietrich film of the same name. In 1948 came DREAM GIRL for a Betty Hutton picture.

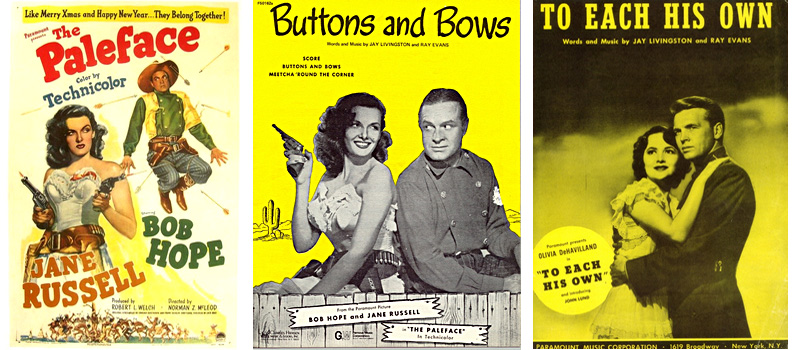

Next assignment on their list was a song for Bob Hope to sing to Jane Russell in “The Paleface”. In the scene in question, Hope was driving a covered wagon, and, when he turned around to sing to Jane in the back of the wagon, his horses took a wrong turn and Bob, Jane and all the wagons behind them ended up in an Indian ambush. This was the only reason for the song. They wrote a song called “Skookum”, which is an actual Indian word meaning (loosely) “OK”. But much to their consternation, director Norman McLeod absolutely refused to use the song, arguing that the Indians were supposed to appear as a menace, a threat, and a comedy song about Indians would botch the scene. Jay and Ray argued that this was a comedy and a big star like Hope was invulnerable. McLeod wouldn’t budge.

Grumbling all the way back to their office, they set back to work and came up with BUTTONS AND BOWS. The song garnered them their first Oscar and, considering that if Norman McLeod had gone with “Skookum”, BUTTONS AND BOWS would never have been written, the guys re-evaluated their idea of McLeod’s musical taste. The song was so popular that the marquee of the Paramount Theater in Hollywood read:

Bob Hope Jane Russell and “Buttons And Bows” in THE PALEFACE

Dinah Shore, very close to giving birth to her first child, recorded the song at three minutes ‘til midnight with the orchestra ad-libbing behind her. At midnight, a planned musician’s strike halted all orchestra recordings for a year. This was the last song recorded before the deadline.

Next up they were assigned a title song for the first Martin and Lewis picture, “My Friend Irma”. Studios love title songs because, if they are lucky enough to get a recording, the picture is plugged every time the song is played. Livingston & Evans became known as “The Song Title Kings”.

But many titles were patently ridiculous and didn’t have a prayer. But, ever faithful, the guys wrote CROSSWINDS and WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE and SANGAREE (they still don’t know what THAT means). Not to mention BEYOND GLORY (they still don’t know what THAT means, either and the lyric, as far as they are concerned, is totally incomprehensible).

The only titles they ever turned down were “Desert Fury” (they gave up on that one) and “Vertigo”. But Alfred Hitchcock was the director of the latter, and he called on them personally for help. He said, “Gentlemen, the studio thinks that no one knows what the word ‘vertigo’ means. But that’s what my picture is about, and if you will write a song explaining what the word ‘vertigo’ means, it will help me a great deal”. So, to please Hitchcock, they wrote VERTIGO, about getting dizzy from the heights, giddy with joy, etc. When they were cutting the demo, Jay decided to see if they had done their job. He asked the singer if he knew what ‘vertigo’ means. The singer replied, “It’s an island in the West Indies, isn’t it”?

In 1949, Alan Ladd was starring in a picture called “O.S.S.” (which was the CIA of World War II). They needed a device to warn Alan Ladd and the partisans in this Italian town that a Nazi patrol was coming. So, as usual, one of the writers suggested somebody sing a song as a warning. It was a pretty unimportant assignment, but they gave it a shot. They wrote a pretty Italian-style song, figuring that the Germans would say “Ja,ja,das ist sehr gemutlich”, and Alan Ladd would say, “Let’s hide the radio and get the hell out of here”. They called the song MONA LISA.

The song was accepted, but a few weeks later, Jay and Ray were called to the front office to be told that the new title for “O.S.S” was “After Midnight”. Of course, they wanted a title song. “Keep that pretty melody”, they said, “but throw out the MONA LISA lyric and write a lyric called ‘After Midnight’”. This didn’t make the writers happy, but they dutifully wrote “After Midnight” and MONA LISA hit the dead song pile. They made a demo of “After Midnight” with the 44-piece Paramount Orchestra, which was expensive and showed how serious they were. But there was a half-hour left on the session, so Jay handed the MONA LISA lyric to the singer and asked him to sing these words to the same melody, “Just for us”.

One day, Jay and Ray picked up Daily Variety and read that the new title for the Alan Ladd picture was now “Captain Carey, U.S.A.” They rushed to the front office and said “You don’t need ‘After Midnight’ anymore. Can we have our MONA LISA lyric back”?

They thought all the Italian singers would jump on it, from Sinatra to Damone to Como. But they all turned it down. Larry Shayne, now in charge of publishing for Famous Music on the West Coast, went after Nat King Cole and never quit. Nat remembered, “I recorded that song to get that Shayne fellow out of my hair”. Capitol (Cole’s record label) didn’t think much of the song and, took full-page ads touting the other side “The Greatest Inventor Of Them All”, a religious song, without even mentioning MONA LISA. It ended up winning Livingston & Evans their second Oscar.

SILVER BELLS is their annuity, however. It has sold well over 160 million records since they first were assigned to write it for Bob Hope and Marilyn Maxwell in 1950 for the Paramount picture “The Lemon-Drop Kid”. The picture takes place in New York at Christmas, and the studio wanted a Christmas song. Jay and Ray balked. “It’s impossible to write a hit Christmas song”, they said.” Every year everybody sings the same old Christmas songs, and new ones never make it”. Also, they were uneasy because they had an option coming up in their contract, and they hadn’t had a hit for awhile. But, as usual, the studio was insistent.

So, with great reluctance, they wrote a song called “Tinkle Bell”, about the Santa Clauses and the Salvation Army workers who stand on New York streetcorners tinkling their bells.

But when Jay told his wife, Lynne, that they had written a song called “Tinkle Bell”, she asked him, incredulously, “Are you out of your mind? Do you know what the word “tinkle” means to most people”? She went on to explain it’s association with a very specific bodily function. Of course, Jay and Ray had never heard it used in that way. “Tinkle” (for “pee”) is a woman’s term. As Jay said in the act that they used to do, “When I was a boy, I said ‘Pee-pee’. Come to think of it, I STILL say ‘Pee-pee’, only more frequently”. They put aside “Tinkle Bell” and started to write a new song. But they liked the music and melody of “Tinkle Bell”, so they just changed “Tinkle” to “Silver”, and the money’s been pouring in ever since. To give the song added dimension, they wrote the verse and chorus so that they could be sung at the same time, and even added a lyric counterpoint to the chorus.

Bing Crosby made the first record, using all these musical tricks. Jay and Ray think this helped the song get started, besides the fact that it was about the city, while most Christmas songs were about home and hearth. They also purposely put it in three-quarter time, in contrast with most other Christmas songs around.

1950 was also the year in which the film “Sunset Boulevard” was released (containing a Livingston & Evans number entitled “The Paramount Don’t Want Me Blues”. Seldom, if ever, before has a movie undertaking to reveal a facet of behind-the-scenes Hollywood attained the entertainment quotient, the emotional wallop and the financial potentialities of this offering from the celebrated team of Producer Charles Brackett and Director Billy Wilder, who — with one collaborator — were responsible also for the screenplay. A masterfully adroit projection of a bizarre, fictional-but-possible film colony situation, the picture still keeps spectators spellbound, while their reactions shuttle with lightning speed of the story’s constantly changing aura of pathos, satire and humor. Performances generally are excellent, most especially that of Gloria Swanson. But the most sterling credit goes to writing and direction. They make the feature truly terrific — and a trifle terrifying.

JUST A MOMENT MORE was written in 1951 for Hedy Lamarr to sing in a Bob Hope pic entitled, “My Favorite Spy”. Jay and Ray assumed that Hedy’s voice would be dubbed, but her contract said that she must sing any songs in her pictures. The range was too wide for her, so Jay had to change a note to make it easier, which, according to him, ruined the melody. The recording was a disaster, but the musical director assured them that all would turn out fine. Later, the studio brought in a good singer to replace Hedy’s voice, and everything sounded swell.

At the preview of the picture, Hedy Lamarr turned to the person seated next to her and said, “I sound good, don’t I”?

When assigned to write “a popular song of India” for the Alan Ladd picture “Thunder In The East”, Jay had no idea what a popular song of India should sound like. But the Paramount music library was a tremendous help to the whole department, and Jay found a new album that had just come in from India. Every song had the same flavor; they all went from major to minor to major to minor, ad infinitum, and Jay used this device for the melody. Ray came up with the title THE RUBY AND THE PEARL.

As they were playing it for the director, a tall, white-clad Sikh in a turban walked in and stood by the door listening. He was the technical advisor. The director, Norman McLeod, said” That’s very pretty. What do you think, Ahmed”? The Sikh said disdainfully, “It’s terrible. It’s all wrong”. Livingston & Evans asked defiantly, ”What’s wrong with it”? The Sikh replied, “In India, we would never compare our love to the ruby and the pearl”. When asked what he would compare it to, the Sikh answered.” To the white orchid and the cockatoo”. It stayed THE RUBY AND THE PEARL .

Strangely, songs have different lives in different countries. THE RUBY AND THE PEARL was never a hit in America, but went #1 in Brazil.

In 1955, Alfred Hitchcock was making a picture called, “The Man Who Knew Too Much” and wanted Jimmy Stewart for the lead. Stewart’s agents, the omnipotent MCA, told Hitchcock he could have Stewart only if he took another client, Doris Day, and another of their clients, Livingston & Evans, to write a song for her. Livingston & Evans insist this is the only time an agent ever got them a job.

Hitchcock didn’t want Doris Day, although he was very happy with her later. He told Jay and Ray that he didn’t want a song, but, he said, Doris is a singer, and the studio wants a song for her. He added, ”I don’t know what kind of song I want. But Jimmy Stewart is a roving ambassador and it would be nice if the song had some foreign words in the title. Also, in the picture, I have it set up so that Doris sings to their little boy”.

It just so happened that Jay had seen a picture called “The Barefoot Contessa”, and at the end of the picture Rozzano Brazzi took Ava Gardner to his ancestral home in Italy, and carved in the stone was the legend CHE SERA SERA. He told her that it was their family motto and meant “What will be, will be”. Jay wrote the title down in the dark. Later, they changed the Italian “che” to the Spanish “que” because of so many Spanish-speaking people in the world. The phrase is also “Que sera sera” in French, which may account for the song’s wide acceptance.

When Jay played the completed song for Hitchcock, the director said, “Gentlemen, I told you I didn’t know what kind of song I want. That’s the kind of song I want”. And he walked out and they didn’t see him again for years.

Meanwhile, there was a Livingston & Evans song in “The Man Who Knew Too Much” that Doris Day really liked and which she recorded (“We’ll Love Again”). However, she refused to record QUE SERA SERA because she thought it was a children’s song. But this was the important song in the picture, so Paramount insisted that she record it. Paul Weston, who was present at the recording session, said that she knocked it off in one take and said, “That’s the last time you’ll ever hear that song”.

Daily Variety and most of the smart money said that Cole Porter, because he had never received an Oscar, was a lock for his “True Love” in 1956’s Academy Awards. But to Jay and Ray’s surprise, their names were called out and they won their third Oscar for QUE SERA SERA.

TAMMY is another famous Livingston & Evans title song. It was written for Debbie Reynolds to sing in the Universal picture, “Tammy and The Bachelor”. The Debbie Reynolds record was a huge hit, and the song received an Oscar nomination in 1957. When they didn’t win, the president of the Motion Picture Academy told them they didn’t receive the award because of a promotion Universal sent out to all Academy members: a letter written in a girl’s handwriting and signed, TAMMY, asking for votes. The Academy members apparently resented this blatant advertising, although today this sort of thing is rampant.

Another song nominated for an Oscar was ALMOST IN YOUR ARMS, written for Sophia Loren to sing in the Paramount Picture, ”Houseboat”, which also starred Cary Grant.

In the late fifties, the writers of the background scores suddenly rebelled and insisted on writing the music for all the songs in the pictures they scored, thus effectively destroying the motion picture activity of the professional songwriters. This was almost the end for great music songwriters like Harry Warren, Sammy Fain, Jimmy Van Heusen and others. But lyricists were in great demand, so, since Livingston & Evans wrote lyrics together, they decided to continue their motion picture activities by writing lyrics for other composers, which they did quite successfully.

One of these, DEAR HEART, which they wrote with Henry Mancini, received an Academy nomination. Other Mancini lyrics include IN THE ARMS OF LOVE, DREAMSVILLE, and BYE-BYE (the “Peter Gunn” theme), and MR. LUCKY, Mancini’s theme for that TV show. They have also written lyrics for picture themes by Max Steiner, Victor Young, David Raksin, David Rose, Percy Faith, and Neil Hefti.

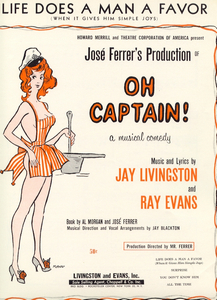

In 1958 Livingston & Evans were assigned to write the score for a Broadway show, OH CAPTAIN!.

Written and directed by Jose Ferrer, and starring Tony Randall and Abbe Lane, it was based on the Alec Guiness film, “The Captain’s Paradise”. The show got mostly rave reviews and everyone was happy, until a man came across the river from New Jersey and demanded to know why he wasn’t getting any statements, as he was an investor. But his name didn’t appear on the rolls, and that’s when the creative team knew that one of the producers was a crook. He simply pocketed the man’s money, and otherwise dipped in the till at random. The show ran for six months and then closed to a full house because there was no money to pay the actors. There have been a hundred different recordings from OH CAPTAIN!, including six different albums of the entire score.

A second Broadway show, LET IT RIDE, starred George Gobel and Sam Levene. A new version of this show was produced by the All Souls Players, an off-Broadway group that has been producing plays and musicals since 1963. It opened on January 31, 1991. The York Theatre Company did a staged reading of OH CAPTAIN! in 1995 in New York in which a talented company read the book and sang the songs.

Livingston and Evans wrote THE SUGAR BABY BOUNCE for the hit Broadway show, “Sugar Babies”, starring Mickey Rooney and Ann Miller. WARM AND WILLING, originally written with Jimmy McHugh for a 20th CenturyFox picture, is also in the show, which is still playing on the road. They wrote special material for Bob Hope’s personal appearances since 1947. They also wrote special night-club material for Betty Hutton, Joel Grey, Mitzi Gaynor, Cyd Charisse, Polly Bergen, and others. They also wrote material for many charity shows; the most prestigious is the annual SHARE Boomtown Party, for which they provided music and lyrics for twenty years. They also did benefit appearances with their “And-Then-I-Wrote” act. This act was of professional quality, and they appeared with stars like Bob Hope, Milton Berle, George Jessel, Carol Burnett, and Helen Reddy.

In 1995, Livingston & Evans received their star on the Hollywood Boulevard Walk Of Fame.

In 1995, Livingston & Evans received their star on the Hollywood Boulevard Walk Of Fame.

In 1996 the Motion Picture Academy honored them with an evening of their songs and accomplishments, including film clips and live performances at the Sam Goldwyn Theatre. Also in 1996, the City of Los Angeles dedicated their annual Music Week to Livingston and Evans, along with Peggy Lee and Joe Williams. The same year, the Young Musicians Foundation, which discovers and helps train young concert artists, presented an evening honoring Jay Livingston, giving him their Lifetime Achievement Award because of the work he has done over the years to help them.

In 1996 Columbia Records released two CD’s containing twenty-three Livingston and Evans songs in their Great American Composers series.

Ray Evans, who is a Wharton School graduate and handy with numbers, keeps meticulous books on the sales of their songs, and has come up with the following statistics: Livingston and Evans have had twenty-six songs that have sold over a million records or more, and the total record sales of their songs has exceeded 400 million.

Sadly, Jay Livingston passed away on October 17,2001 and Ray Evans passed away on February 15, 2007.